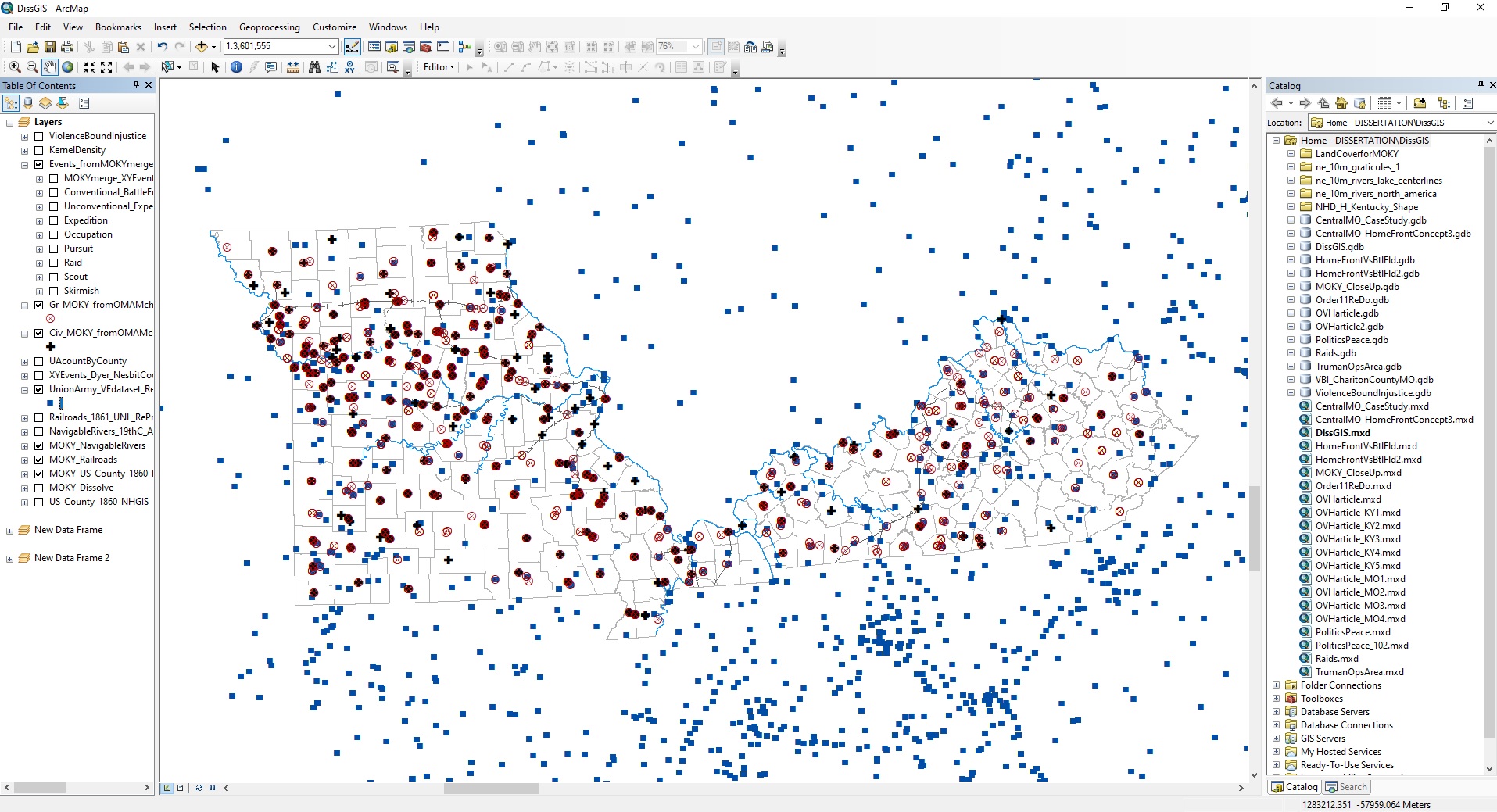

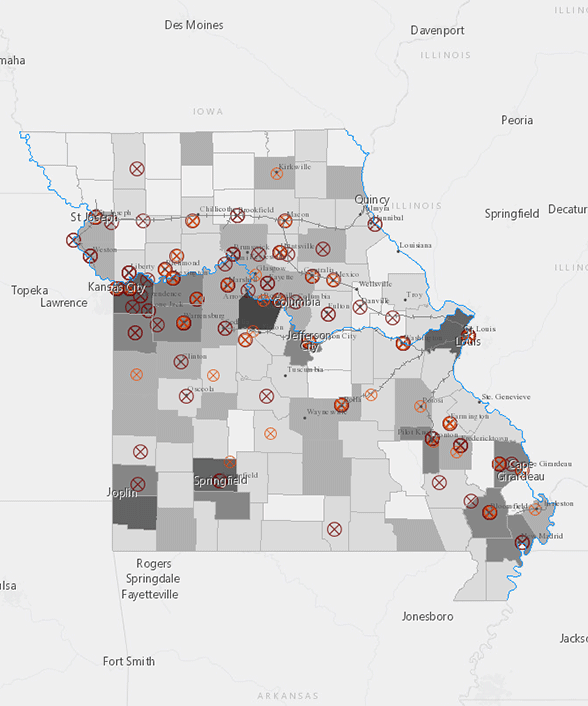

....historians couldn’t make a map of guerrilla war until the advent of digital mapping techniques—the guerrilla war’s size and scope was too big for traditional mapmakers.

Not only did guerrilla violence influence the conventional war’s conduct... it created a unique household war zone that swallowed any person—commander, soldier, vigilante, guerrilla, or citizen—living in occupied territory.

Using a CD-ROM version of the OR, I keyword-searched all 128 volumes using a list I created with the assistance of historians Matthew C. Hulbert, Patrick Lewis, and Joseph M. Beilein, Jr. That list is as follows, with the number of times each keyword appeared in the OR immediately following:

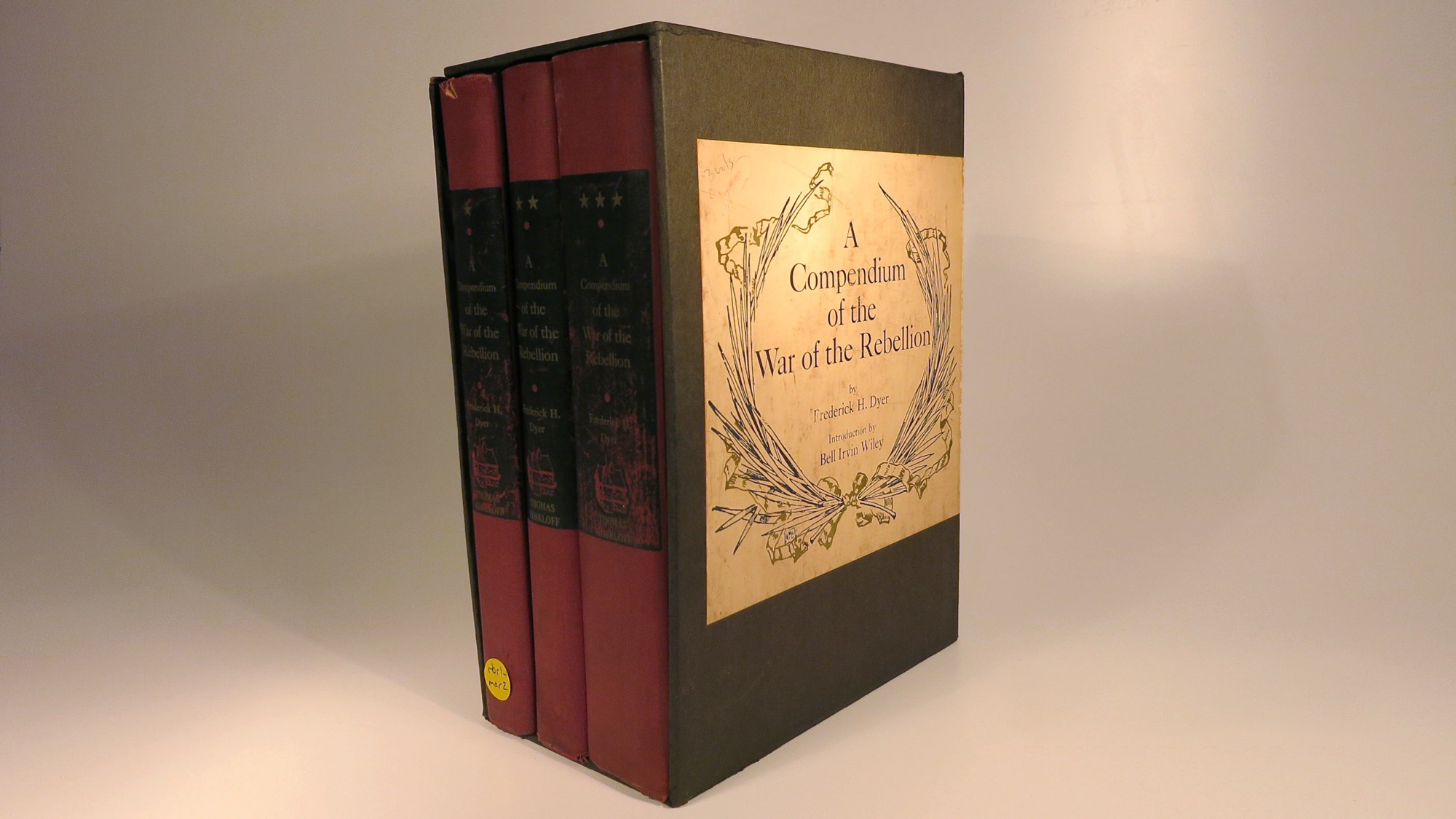

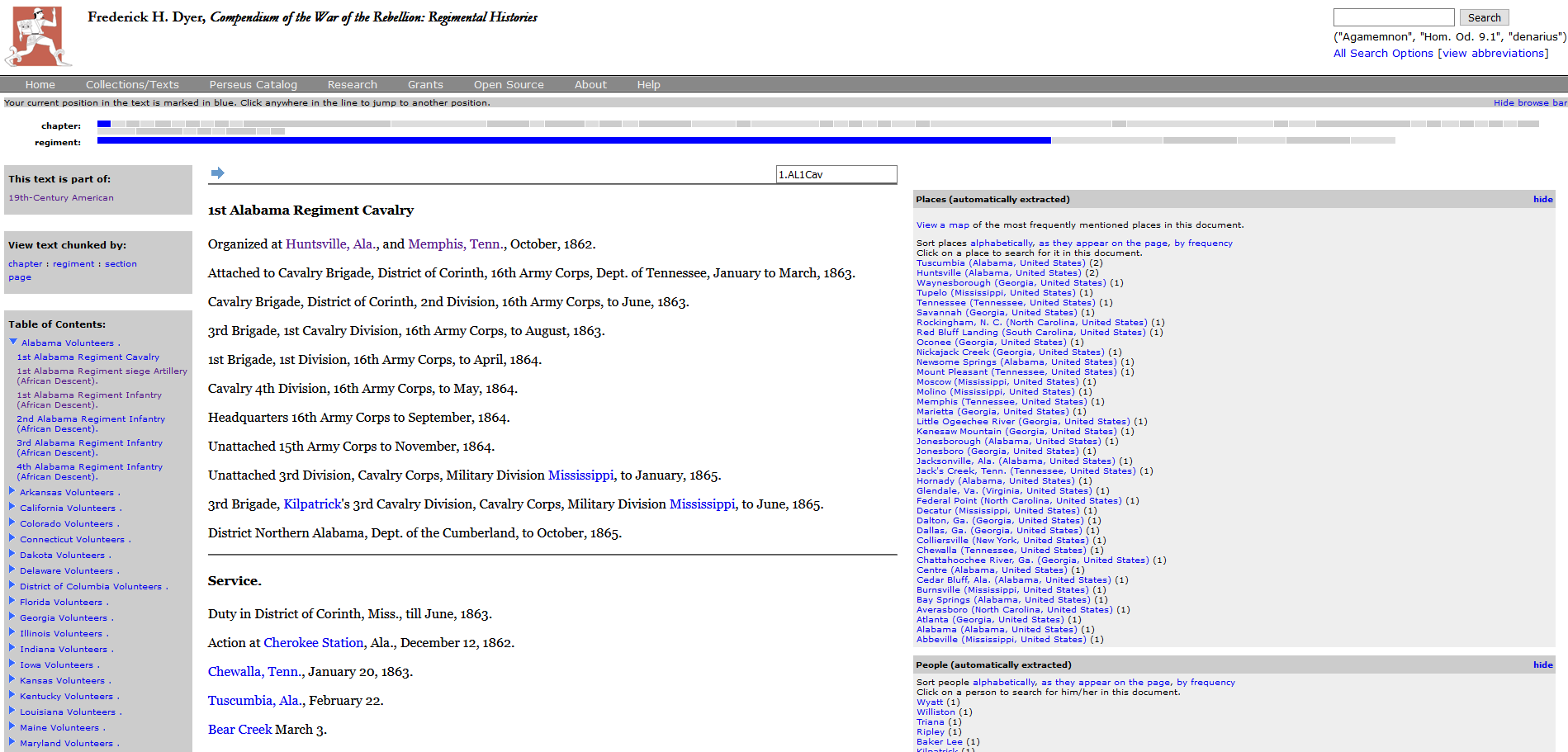

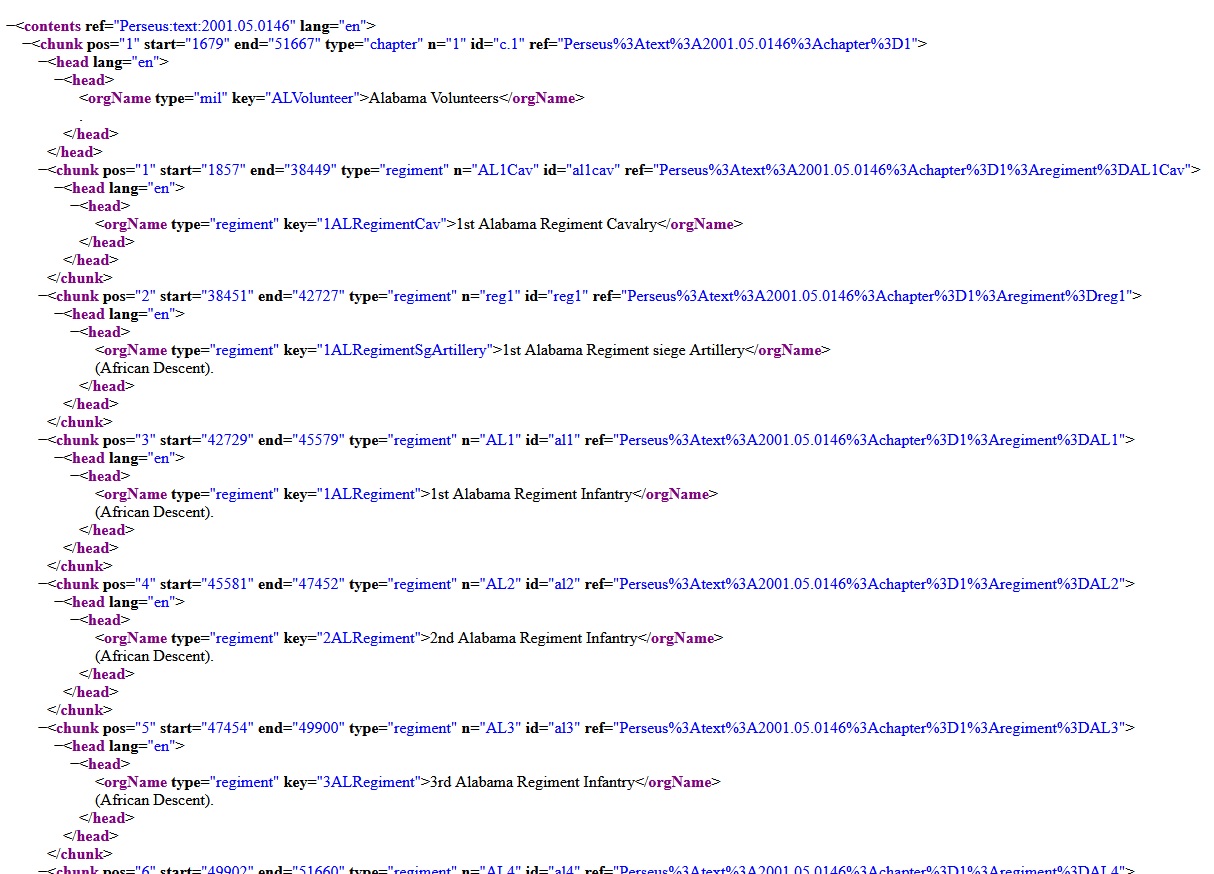

It is important to note that keywords related to Frederick Dyer’s language for the Union’s tactics that were often irregular—scout (23,581); recon (13,017); expedition (19,277)—returned so many hits that only a separate project dedicated to mapping the Union’s company-level movements (and cross-checking Dyer’s Compendium to ensure no repeated information) could adequately map them. I did catalogue instances of these Union movements when they appeared in documents associated with the above list.

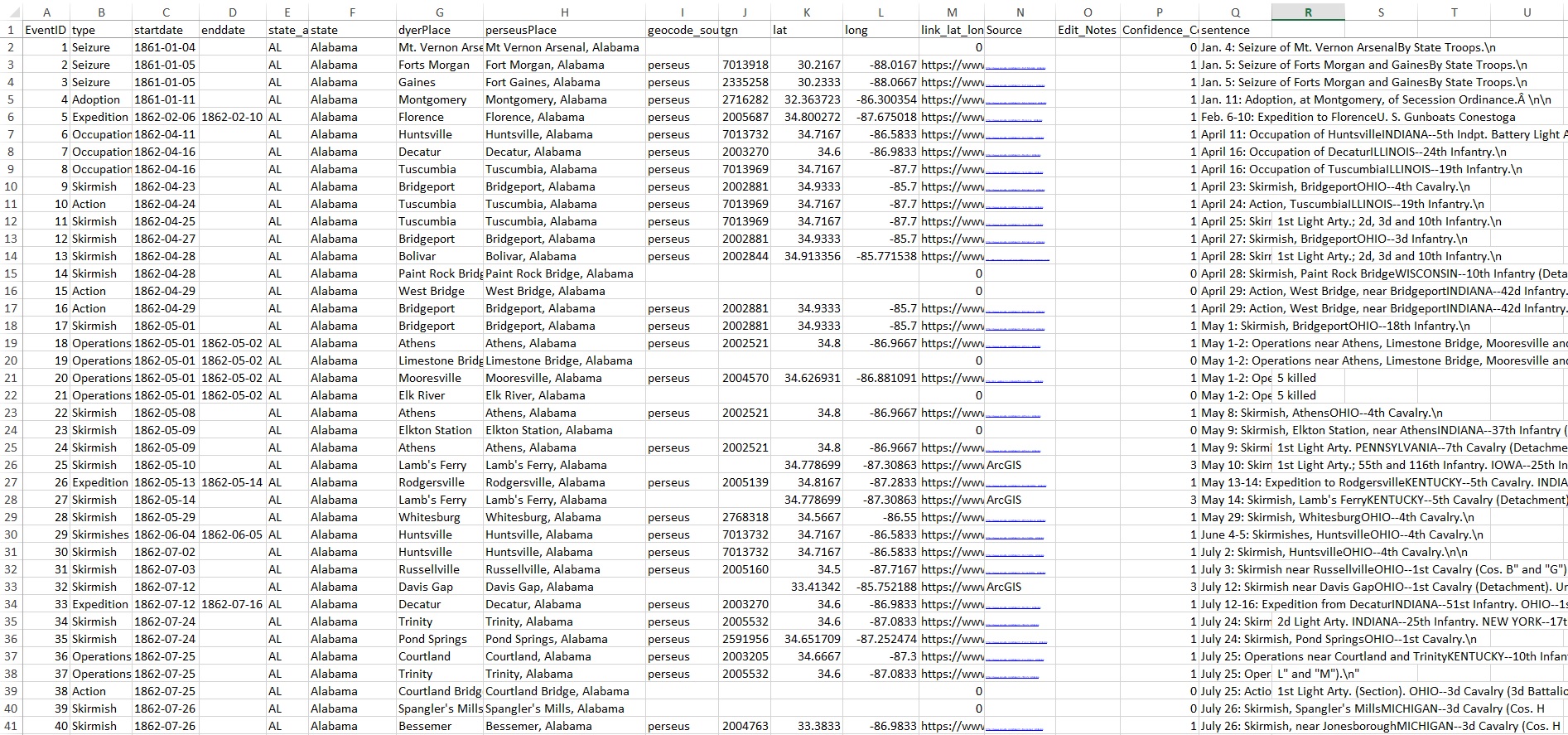

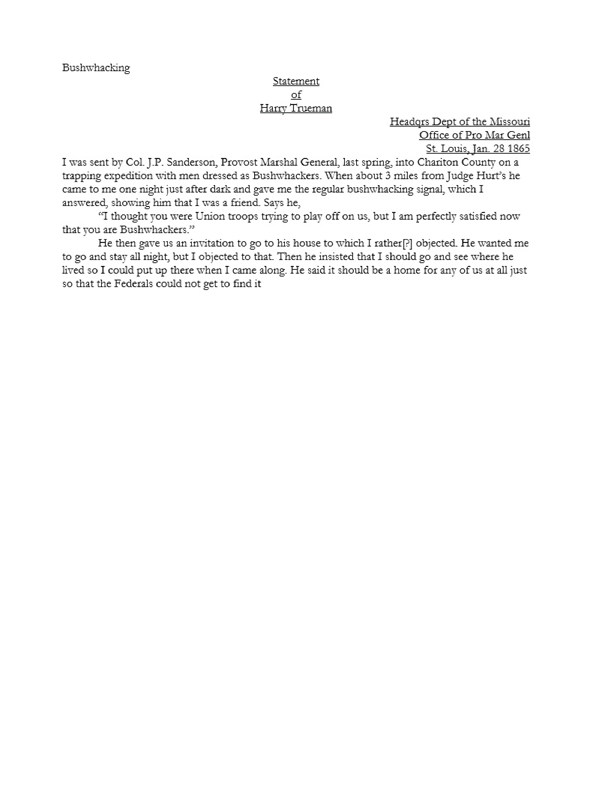

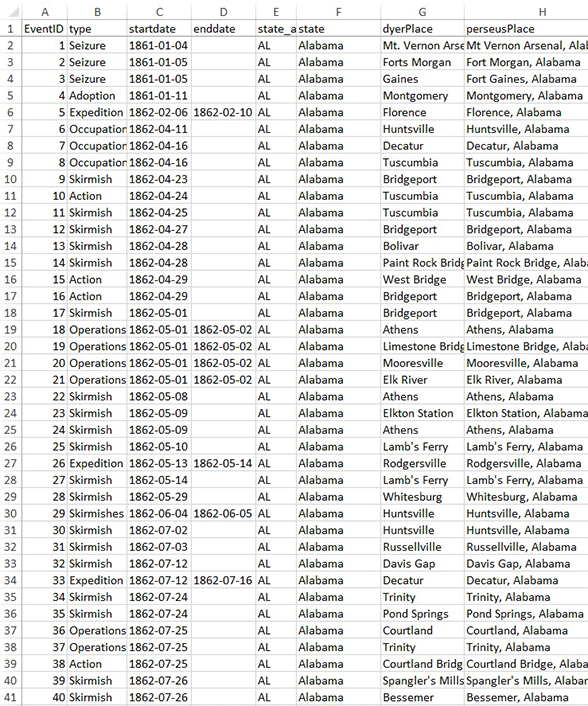

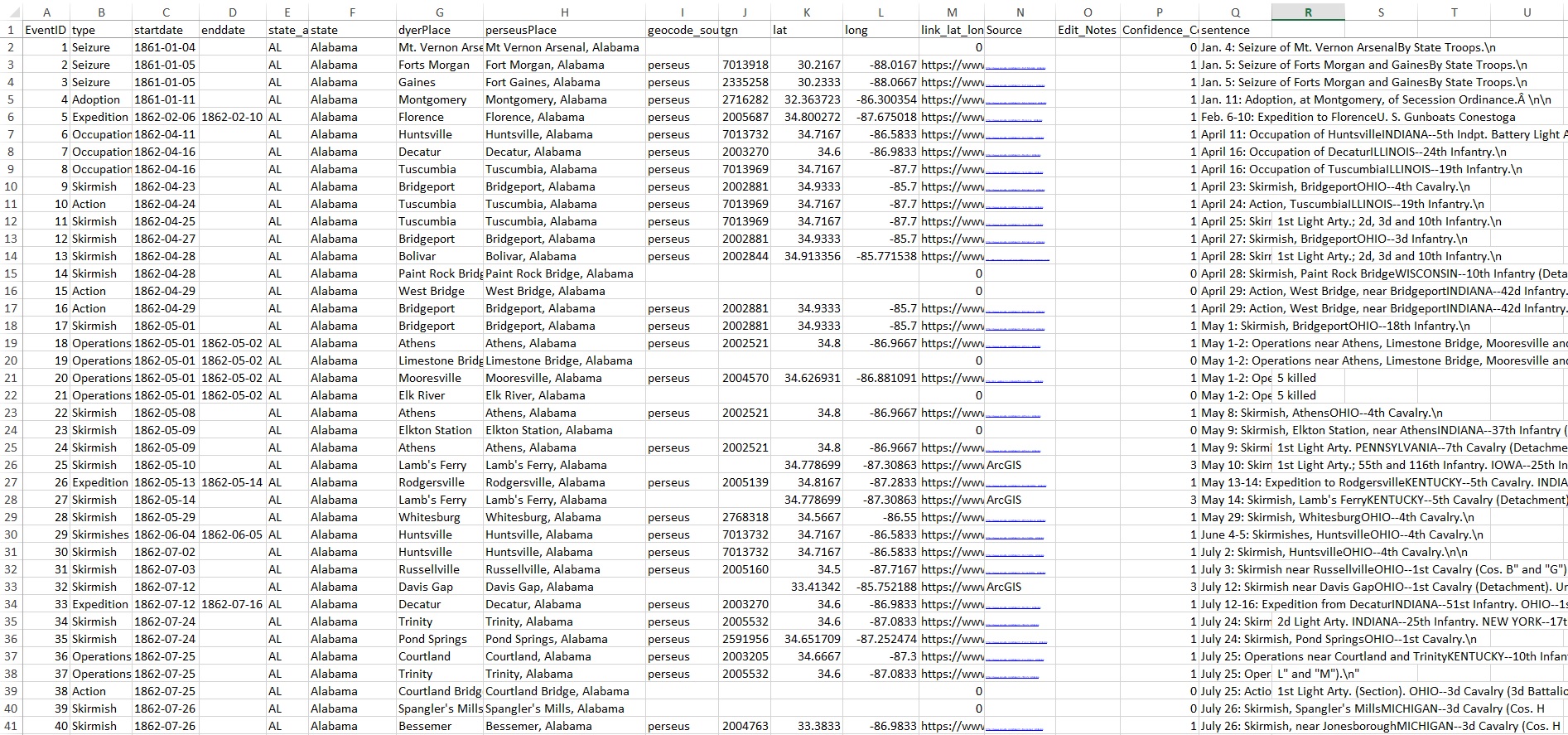

I then began the two-step process of datafication. First, using physical volumes of the OR, I read the documents associated with these keyword searches. Next, I indexed any instances of guerrilla violence, civilian aid, or Union army activity, by necessarily manipulating that evidence to fit in a database. What follows is an explanation of that process and a screenshot of the actual database.

Antoine-Henri Jomini, The Art of War (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1971 [original 1862]), 29; Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Washington, D.C.: Combat Forces Press, 1943 [original 1832]), 3-4, 53-55, 547-462. ↩

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and the Confederate Army, 128 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1880-1902). ↩

Yael A. Sternhell, “The Afterlives of a Confederate Archive: Civil War Documents and the Making of Sectional Reconciliation,” Journal of American History 102, no. 4 (March 2016): 1026, 1044, 1048-1049. ↩

Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (New York: Sagamore Press, 1908). Quotes from Bell Irvin Wiley’s introduction to the 1959 edition [unnumbered pages]. The unused Volume II is a “Name Index of Commands” detailing every Union officer, their rank(s), the dates they held said ranks, and their regiment’s associated brigade, division, corps, and army. ↩

Gregory R. Crane, “Perseus Digital Library,” Tufts University, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/ (accessed March 20, 2020). ↩

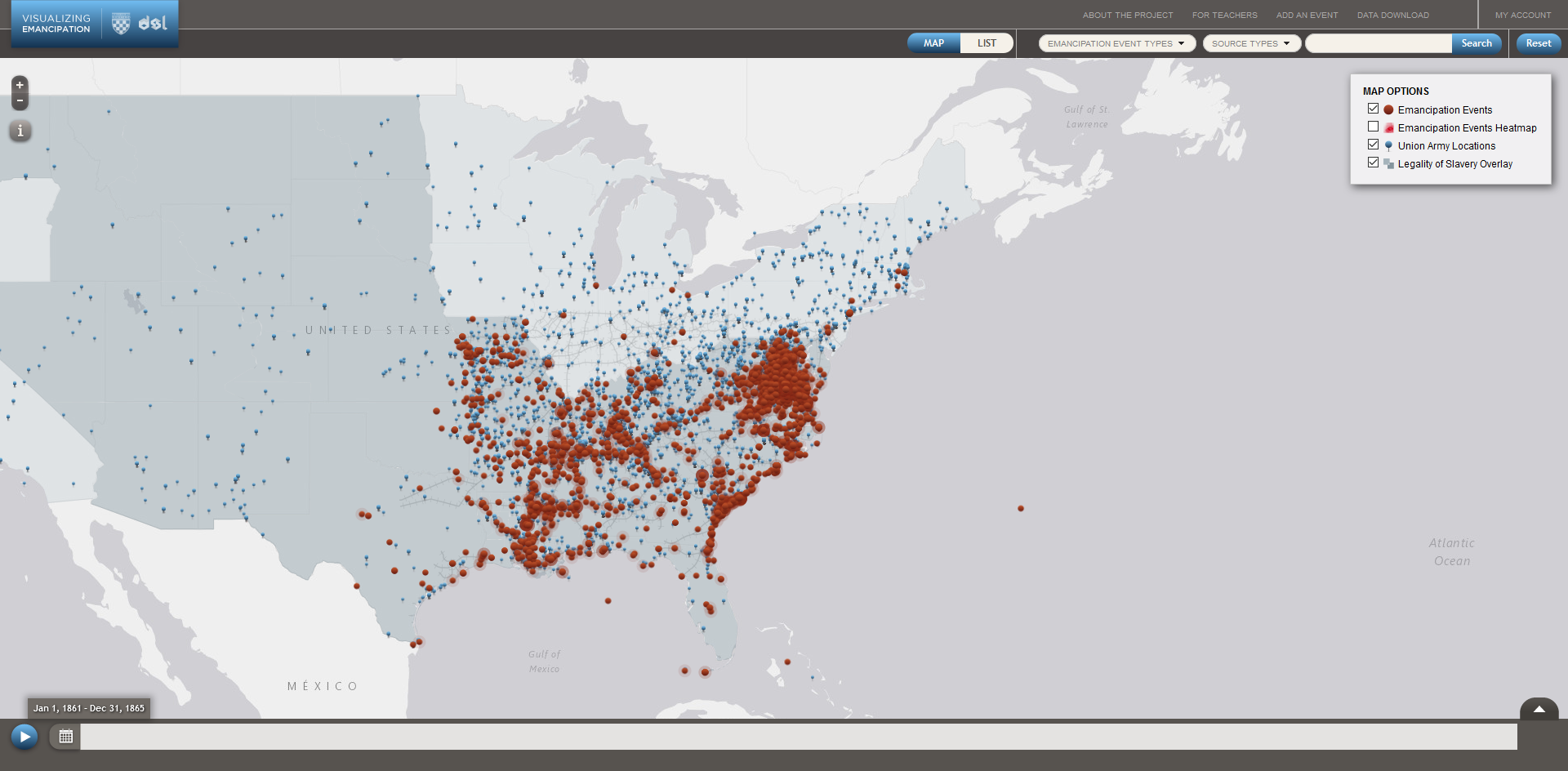

The University of Richmond, “Digital Scholarship Lab,” Boatwright Memorial Library, Visualizing Emancipation, http://dsl.richmond.edu/emancipation/ (accessed March 20, 2020). “Visualizing Emancipation” credits the following for transforming the digitized text of Dyer’s Compendium into mappable data: “Chris Kemp has provided help in working with xml-encoded texts and their transformations, and played a significant role in transforming the Union army information from textual description to mapped data. … Alex Wan helped clean U.S. army data that had been generated algorithmically.” See http://dsl.richmond.edu/emancipation/credits/ (accessed March 20, 2020). ↩

Dyer actually used 154 different terms to describe the Union army’s movement, but I removed misspellings, different tenses of the same verbs, and plurals of the same verb. I used nineteenth-century United State military manuals to better understand Dyer’s terminology. See, William Duane, A Military Dictionary, Or, Explanation of the Several Systems of Discipline of Different Kinds of Troops, Infantry, Artillery, and Cavalry; The Principles of Fortification, and All the Modern Improvements in the Science of Tactics: Comprising The Pocket Gunner, or Little Bombardier; the Military Regulations of the United States; the Weights, Measures, and Monies of All Nations; the Technical Terms and Phrases of the Art of War in the French Language, Particularly Adapted to the Use of the Military Institutions of the United States (Philadelphia, 1810); and Captain Lendy, Maxims, Advice and Instructions on the Art of War, or a Practical Military Guide for the Use of Soldiers of All Arms and of All Countries (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862). ↩

Andrew Fialka, email to Perseus Digital Library’s Managing Editor, September 25, 2017. The Perseus Digital Library used Prime Recognition for its Optical Character Recognition software. See “Prime Recognition,” http://www.primerecognition.com/ (accessed March 20, 2020). ↩

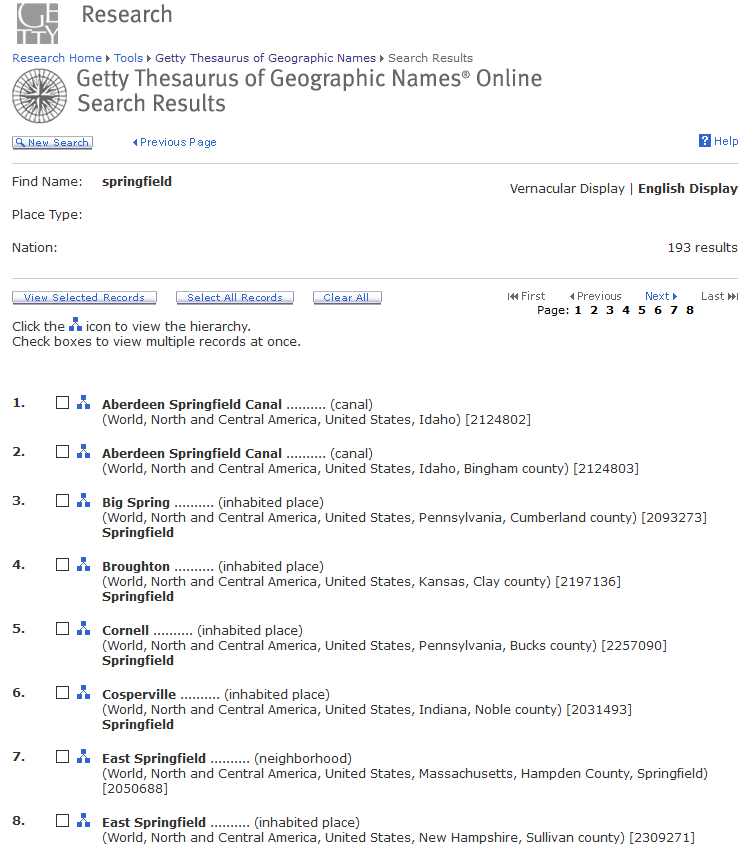

The J. Paul Getty Trust, “Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names® Online,” The Getty Research Institute, http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/

vocabularies/tgn/index.html (accessed

March 20, 2020). See “Methods,”

Visualizing Emancipation, http://dsl.richmond.edu/emancipation/

methods/ (accessed March 20, 2020). The site’s description of geotagging errors in its entirety is as follows: “errors appeared during the process of identifying placenames; some historical places

are not listed in even the best modern

gazetteers, while other places remained

ambiguous to the computational models

because they are shared by multiple locations. For more information on the digitization and data extraction process, see ***. The Digital Scholarship Lab introduced further errors in computationally pairing dates and locations. While we have caught hundreds of errors, we know that many others still remain to be corrected. We are currently looking for ways to correct remaining errors in the armies dataset.”

↩

For NHGIS’s description of its source

material, see NHGIS, “What is the source of

NHGIS data?,” Frequently Asked Questions, https://www.nhgis.org/user-resources/faq#data_source (accessed March 20, 2020) and NHGIS, “Tabular Data Sources,” https://www.nhgis.org/

documentation/tabular-data (accessed March 20, 2020). In regards to the 1860 Census consulted for this project, research teams headed by Michael Haines, Donald Bogue, and Andrew Beveridge undertook “the arduous conversion of pre-computer-age historical data from print media to a digital, machine-readable form.” These research teams consulted secondary sources in addition to the U.S. Census, including Michael R. Haines, “Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data: The United States, 1790-2002,” Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research Study 2896, University of Michigan, https://www.nhgis.org/

sites/www.nhgis.org/files/histseries-icpsr02896-1790-2002.pdf (accessed March 20, 2020) and William Thorndale & William Dollarhide, Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses 1790-1920 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987).

↩

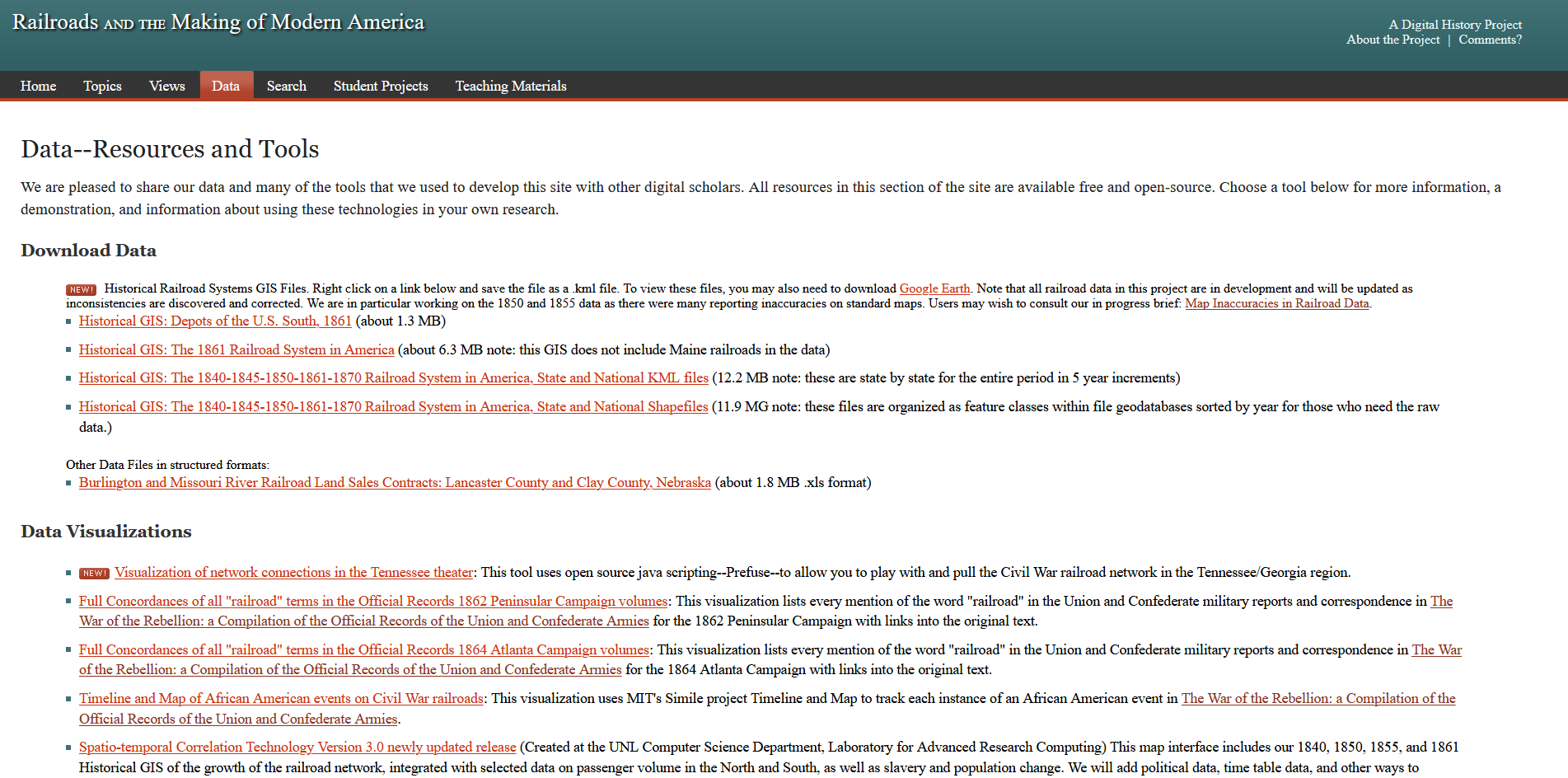

See “Map Inaccuracies in Railroad Sources,” Railroads and the Making of Modern America, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, http://railroads.unl.edu/views/item/mapping (accessed March 20, 2020). Davis, George B., Leslie J. Perry, Joseph W. Kirkley, Calvin D. Cowles, & Richard Sommers, eds., The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War (New York: Gramercy Books, 1983). ↩

For a thorough discussion of issues relating

to the creation of this dataset, see Jeremy

Atack, “Procedures and Issues Relating to the Creation of Historical Transportation

Shapefiles of Navigable Rivers, Canals and

Railroads in the United States,” Vanderbilt

University, https://my.vanderbilt.edu/

jeremyatack/files/2015/12/Creating-Historical-Transportation-Shapefiles-of-Navigable-Rivers-Revised-December-2015.pdf (accessed March 20, 2020). Natural Earth derived their river data from World Data Bank 2 and “the North American Environmental Atlas, a collaboration of government agencies in Canada, Mexico and the United States and the trilateral Commission for Environmental Cooperation.” Natural Earth also “manually smoothed” their data. For additional information on World Data Bank 2, see Central Intelligence Agency. WORLD DATA BANK II: NORTH AMERICA, SOUTH AMERICA, EUROPE, AFRICA, ASIA. ICPSR version. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Geographic and Cartographic Research [producer], 1977. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2000. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR08376.v1 (accessed March 20, 2020).

↩

Robert R. Mackey, The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005), 13-14. Mackey’s work is one of the most useful for delineating definitions for guerrilla activity. ↩

Fellman, Inside War, 238. ↩

Many can be found in, J. C. Eakin and D. R. Hale, Branded as Rebels: A List of Bushwhackers, Guerrillas, Partisan Rangers, Confederates and Southern Sympathizers from Missouri During the War Years. (Lee’s Summit, Missouri, 1995). In addition, Richard Brownlee’s Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy includes an appendix of “known members of Quantrill’s, Anderson’s and Todd’s guerrillas.” The list includes 340 names and when the guerrillas died. See, Richard Brownlee, Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1958), 253-261. ↩

Michael Fellman provides an excellent examination of this phenomenon, which he calls “survival lying.” See Fellman, Inside War, 58, 264, 49-52, 195, 228. ↩

There are three major exceptions. First, eHistory works closely with David Holcomb of the Information Technology Outreach Services group at the Carl Vinson Institute of the University of Georgia. Because of my association with eHistory, I was able to reach out to David for help on many occasions, especially regarding ArcGIS Online. Second, I hired Brandon Adams—Senior GIS Technician at the University of Georgia’s Center for Geospatial Research—for GIS tutoring using funds from the Horace Montgomery fellowship in 2015. Last, I took a research seminar while at UGA entitled History, Mapping, and Spatial Analysis. While the course represented an eight-week version of the entry-level GIS course I took at WVU, I spent the second eight weeks of the course learning valuable information from the course’s professor: Dr. Sergio Bernardes (also employed with UGA’s Center for Geospatial Research). My sincerest thanks to all these men. ↩

George Mason University, “Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media,” http://omeka.org/ (accessed March 22, 2020). ↩

For more information on Dublin Core standards, see, University of Tsukuba, Japan, “Dublin Core Metadata Initiative,” http://dublincore.org/ (accessed March 22, 2020). ↩

For more info, see ESRI, “ArcGIS Online,” https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/overview (accesses March 22, 2020). ↩

Footnotes 61 and 63 from Andrew Fialka, “Controlled Chaos: Spatiotemporal Patterns within Missouri’s Irregular Civil War,” in The Civil War Guerrilla: Unfolding the Black Flag in History, Memory, and Myth, Joseph Beilein, Jr. & Matthew C. Hulbert, eds. (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2015), 61, 64. ↩

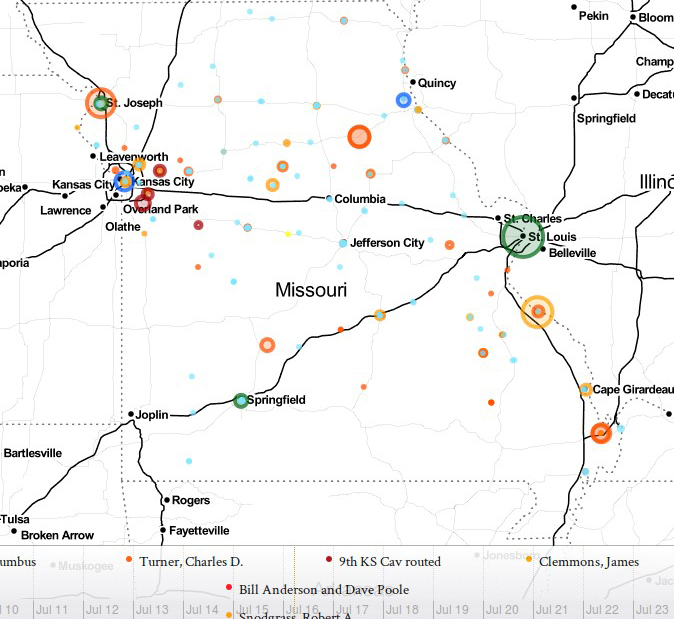

1) follow the link to ‘Interactive Map with Accessible Database’; 2) Click ‘Content’ to pull up a menu where you can toggle off and on the map’s layers; 3) Expand the ‘Of Methods and Madness’ menu by clicking on the gray triangle next to ‘Of Methods and Madness’; 4) Scroll down to the layer entitled ‘Primary Source Data Displayed by City (Time)’; 5) Click on the ‘Show Table’ icon below any of the subfields in that layer. ↩